Let me start by saying I’m a Netflix fan. Where else will you find 12, a Russian retelling of the movie, Twelve Angry Men, next to Helvetica, a documentary on the most pervasive font in the world? Not at my local Blockbuster, that’s for sure.

Let me start by saying I’m a Netflix fan. Where else will you find 12, a Russian retelling of the movie, Twelve Angry Men, next to Helvetica, a documentary on the most pervasive font in the world? Not at my local Blockbuster, that’s for sure.

My love affair with movies goes back to my childhood. When I was nine, my parents took me to see My Side of the Mountain and ever since I have kept my eyes open for a tree big enough to hollow out and live in. Later, my uncle took my sister and me to the Killarney Drive-In to see Paper Moon, Tatum O’Neal’s Oscar-winning debut. And then in a spectacularly daft move, I took my straight-laced parents to see Bill Murray’s movie, Stripes, thinking my dad would like it since he had been in the Army.

For me, Netflix has been too good to be true. It brought me a 160-minute movie about a French monastery without any dialogue, Into Great Silence, and a film in Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan, called Travellers and Magicians. I’ve enjoyed a Columbian movie called The Wind Journeys, a Faustian tale about an accordion-playing troubadour, and I’ve watched so many Scandinavian movies on Netflix, I now have a favorite Danish actor (Mads Mikkelsen). The world’s best cinema is just a mouse click away.

So when this innovative company with a passionate following raised prices and separated DVD and streaming services into two separate payment plans, the ensuing outrage was predictable.

And just yesterday, the Netflix CEO added insult to injury when he announced in a faux-folksy blog post that he is splitting the DVD-by-mail service and streaming video businesses completely. That means two bills, two separate movie queues. Netflix will remain the name of the streaming business, and they have chosen the unfortunate name of Qwikster for the DVD service.

It’s not just the 60 percent increase in prices that has customers riled up.

If the streaming options were more plentiful, this wouldn’t be getting the same reaction. Many users relied on the mix of DVDs and streaming since many movies weren’t available for instant viewing. And that gap will get worse since Starz Entertainment declined to renew its streaming agreement with Netflix last month, which means the company would lose online access to movies from Sony and Disney.

A clever analogy showed up in a Netflix story on the National Public Radio website this morning:

It’s like a shoe company deciding to sell right shoes and left shoes for 12 dollars each where pairs of shoes used to be 20 dollars and thinking that customers will notice the 12-dollar price but not the fact that it buys only one shoe.

How do smart companies make such dumb moves? How does Netflix go from being Cinema Paradiso to Little Shop of Horrors?

Back in 2002, Scott Bedbury cast a wide net when he described the elements that make up a company’s brand in his book A New Brand World:

A brand is the sum of the good, the bad the ugly, and the off-strategy. It is defined by your best product as well as your worst product. It is defined by the accomplishments of your best employee – the shining star in your company who can do no wrong – as well as by the mishaps of the worst hire you ever made. It is also defined by your receptionist, and the music your customers are subjected to when placed on hold. For every grand and finely worded public statement by the CEO, the brand is also defined by derisory consumer comments overheard in the hallway.

Since social media didn’t exist as we know it when Bedbury wrote this book, you can easily replace the last phrase with “the brand is also defined by derisory consumer comments on Twitter and Facebook.” In today’s environment, when you have zealous advocates for your product, changes you make that loosen that bond can reverberate in social media space with a vengeance.

The fine folks at Netflix should have read Bedbury’s book. His credentials are pretty impressive. He was senior vice president of marketing at Starbucks from 1995 to 1998. Prior to that he was head of advertising for Nike, where he launched the “Bo Knows” and “Just Do It” campaigns.

The outcry of disenchanted Netflix customers is vitriolic, but analysts are pooh-poohing the response as not indicative of the majority of users. But the drop in stock price from a high of around $300 per share this summer to $143 today begs to differ. And while its subscriber forecast is for 24 million customers — that’s down 1 million customers from just a few weeks ago.

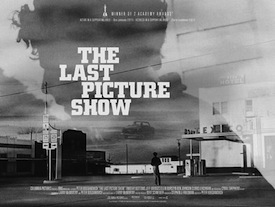

At this rate, their coming attraction just may be The Last Picture Show.